Everyone was looking forward with eager anticipation to visit the famous Sheats-Goldstein House that had been featured in so many commercials, magazines, and a number of movies such as Charlie’s Angels or The Big Lebowski. After getting an elaborate guided tour from James Goldstein’s assistant Roberta Leighton, we could gain a deeper inside into the renowned piece of architecture and our expectations were far exceeded. Not only did we learn about the house itself but also about the owner who is just as striking as his home. When our group gathered in front of the property, Goldstein was just about to leave and drove past us in his ivory Rolls-Royce.

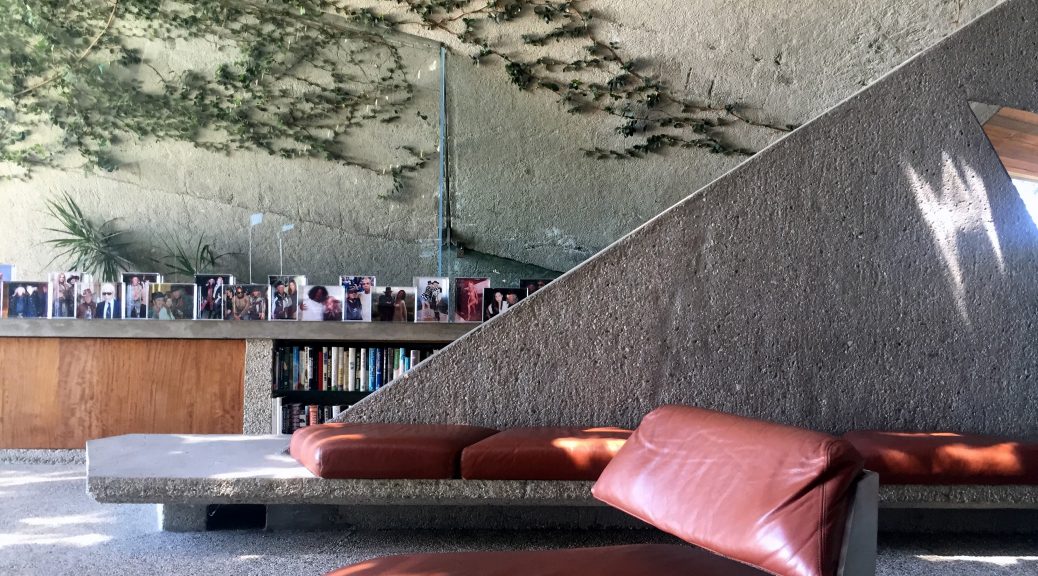

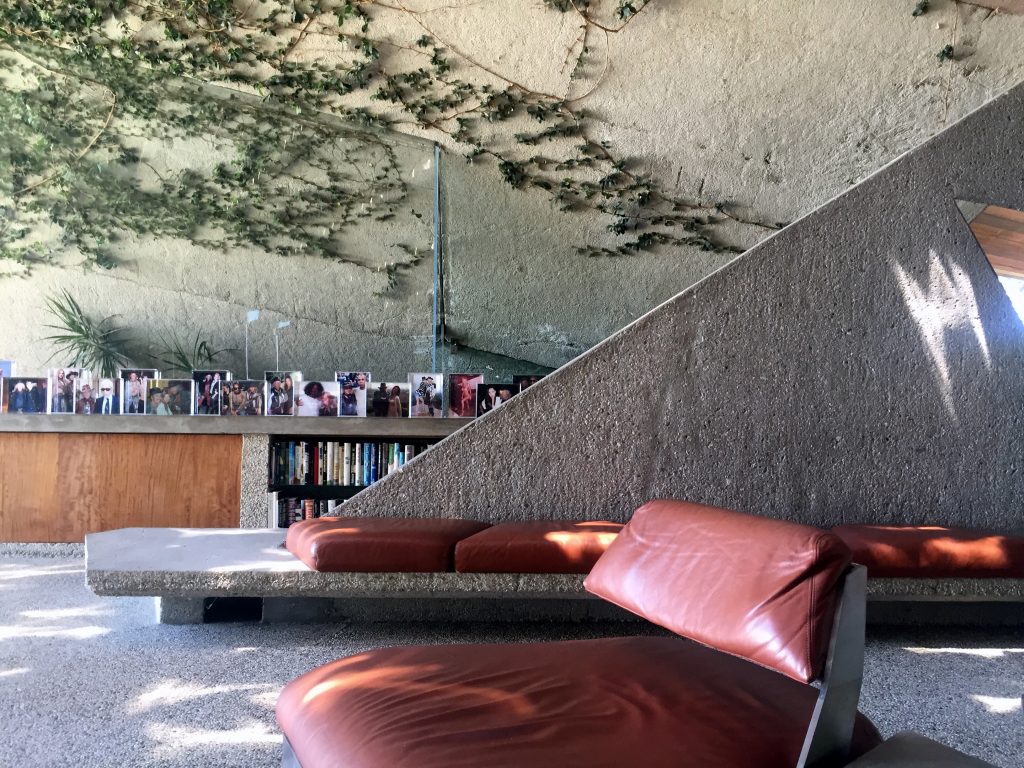

The Sheats-Goldstein Residence sits hidden in the hills of Beverly Crest and is not visible from the streets. To arrive at the imposing house, we had to go down a steep and densely planted driveway where we already got a foretaste of the jungle-like garden that awaited us inside. On entering the structure, we crossed a path of concrete and glass stepping stones with no guardrails leading through a koi pond to the doorway. A large glass wall runs along the length of the walkway and you start to get a sense of the house’s principle characteristic – blending indoor and outdoor space. In this building the exterior is very much part of the interior, which is clearly shown by a lot of dynamic features. Frameless curtain walls open electronically towards Los Angeles and a huge skylight over the kitchen table provides an alfresco dining experience. In the living room, the triangular coffered ceiling with its punctuated glass windows scattering light into the room was even more impressive than expected. The borders between inside and outside seemed to dissolve. Lautner took the indoor-/outdoor architecture to an extreme by installing numerous glass walls and openings that create a feeling of transparency and bring additional daylight into the building.

The living room leads outside to a cantilevered concrete pool deck with magnificent views of Los Angeles and the wildly growing garden surrounding the residence. Goldstein transformed the site into a tropical forest with exotic flowers brought in by air. On a totally secluded residential estate with extensive landscaped gardens, the mansion has a sheltered and elevated character. It feels like the Sheats-Goldstein House is a modern architectural vision in the middle of the jungle. Concrete paths and stairways are leading to several hide aways throughout the property including small terraces and a James Turrell Skyspace art installation.

Attention to detail and passion for exclusiveness is demonstrated throughout the entire structure. With the press of a button, the wooden ceiling opens to let down a large LCD screen and an outdoor spa tub reveals itself from underneath the terrace. The triangular leather lounging areas perfectly suit the architectural style of the house and so does the movable built-in desk chair in the master bedroom designed by John Lautner himself. Right next to Goldstein’s king bed you will see viewing windows for the swimming pool above. Originally they were inserted so that the former owners could watch their children swim from the lower level.

Tour guide Roberta showed us many hidden features like a see-through sink or a scale hidden in the floor to underscore the uniqueness of Mr. Goldstein’s home. As if we weren’t overwhelmed already, she also showed us the later additions to the property and took the tour to its ultimate point. When he bought the house next door to his residence, Goldstein added an infinity tennis court with an incredible panoramic view over the city. Ironically, demolishing a sibling Lautner house was part of the project building the annex which also includes offices for Mr. Goldstein and his assistants, as well as his own private nightclub appropriately named Club James.

Since 45 years James Goldstein and his architects have continuously developed and upgraded the house to a masterpiece of a home. It is hard to believe that this place was initially built for a family. However, it is quite conceivable to picture James Goldstein in this imposing structure. A reason for that might be the fact that the house is filled with self portraits of the basketball and fashion enthusiast. At the turn of every corner there are photos of Goldstein posing with namable celebrities and models.

The home is stacked with magazines and books about architecture, basketball, and fashion. Goldstein’s eccentric designer clothes are proudly on display in the master suite. As a matter of fact his wardrobe, filled with exotic leather jackets, works automatically and with the push of a button, the clothes rack will revolve. It seems like the prestigious property is an architectural self-display of its owner who, together with John Lautner and his successors, reshaped the 1963 home into a total artwork that incorporates Goldstein’s vision. The extensive tour enabled us to experience all the architectural features of this impressive mansion and to learn about the man of the house. James Goldstein’s assistant Roberta Leighton was passionately devoted to show us around and our group greatly appreciated the opportunity to visit such a unique residence which is truly in a class of its own.

Josefine Rauch